“Sometimes I feel like a motherless child. Sometimes I feel like a motherless child. Sometimes I feel like a motherless child, a long way from home,”.

Reading this post may be like sifting through a pile of scattered thoughts. A reflection in itself of the fact that losing a parent is an experience that covers the lifespan. My hope is that you will see it as a continuing conversation, not a final answer. And that you may find some encouragement and strength for your journey.

The loss of a parent may be one of the broadest experiences of loss. No stage of life guarantees us that our parent’s death will go unfelt or unmourned. No stage offers us immunity from feeling that loss, or facing the change it brings.

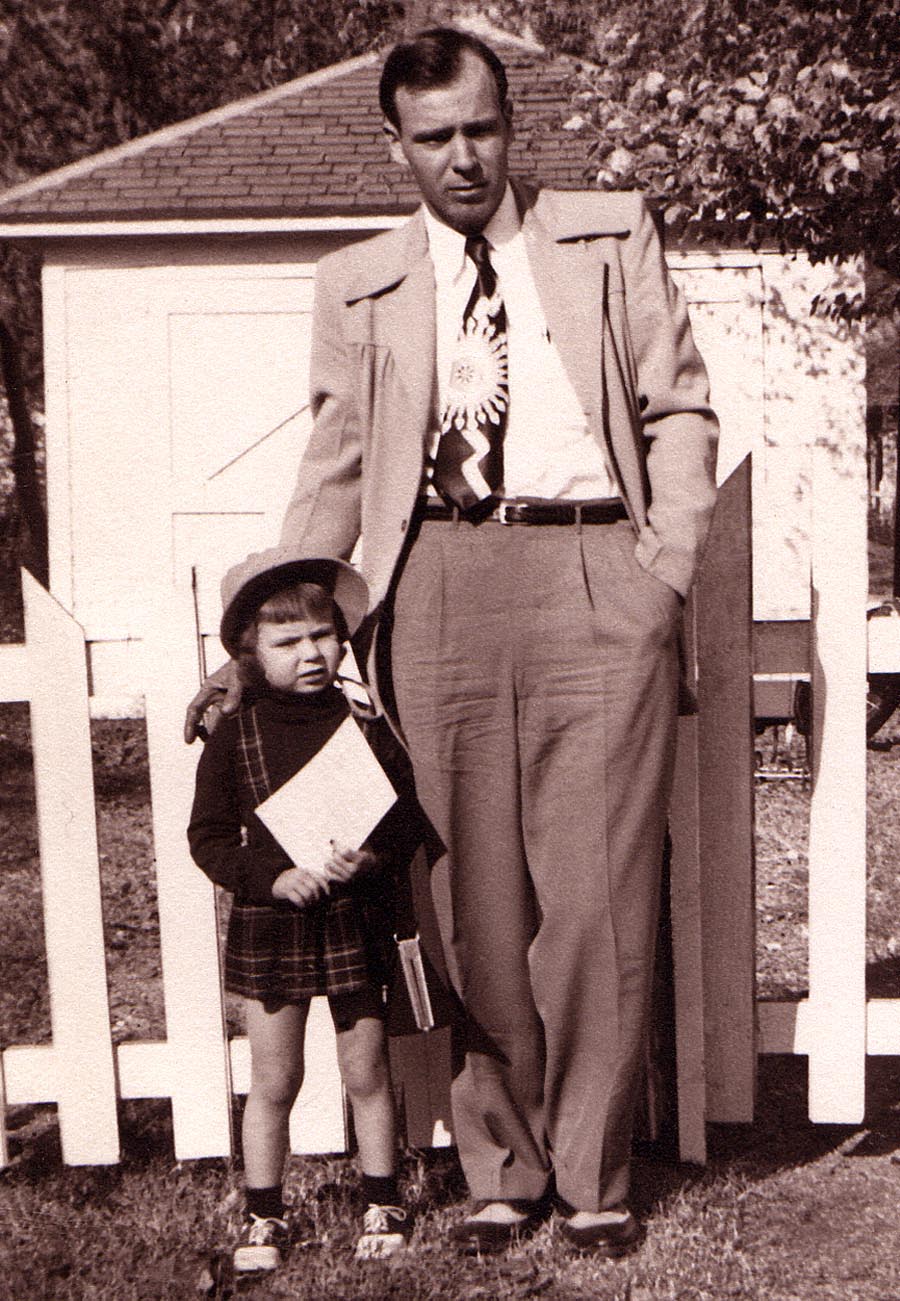

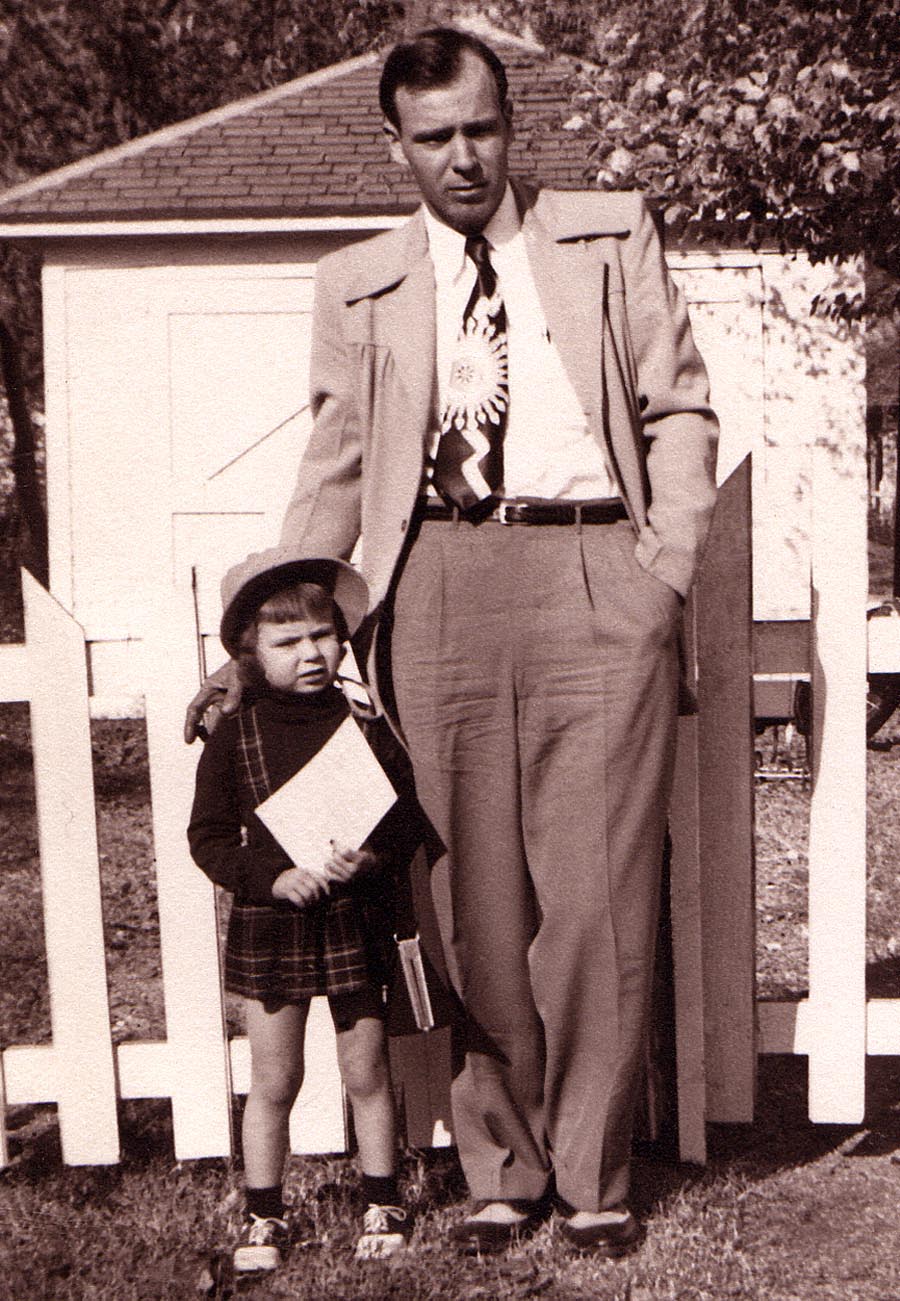

The younger we are the more our loss may encompass grieving the parent we never knew. For a child, the death of their parent can mean living with the nagging feeling of having been left. Not unlike being left on a hiking trail without our guide, before we’re confident of our ability to find our own way. When one parent dies, a child often loses the other parent to their own grief. We may feel isolated as we try to protect the other parent from feeling our shared pain. Sometimes we arrive in adulthood carrying the wounds of childhood losses experienced before we had an older, wiser, more forgiving language. A language to help us both describe and soothe our pain.

The feeling of being left can come at any age. As though the color of abandonment is present for each of us, just in different shades based on the time and circumstances. When my dad’s mother died I recall him saying reflectively, “Now I’m the oldest living member of my family”. There was sadness, resolve, and a touch of uncertainty in his voice. I was surprised. There were ways he had lost her long before that moment, to the dementia that swallowed her up one bite at a time. And even before that when her 13 year son died suddenly from spinal meningitis. She was forever changed, and at age 11 my dad lost his brother and became the oldest son, bearing the weight of hopes and dreams not yet lived. It struck me that all of those losses, sudden and progressive, did not protect him from the finality of that moment. Of knowing that he would never have more of her in this life than had been gathered from his birth up to the time of her death. And that in the starkest of realities, the buck now stopped with him.

Our experience of loss may also be colored by the gap between who we needed our parent to be and who they actually were. We can believe that an abusive parent’s death will bring relief and freedom from our pain, only to discover that in being rid of harm we also lost all possibility that the parent we need would someday appear. Whatever has been left unsaid, the acknowledgement of harm, the “I’m sorry”, the “Please forgive me”, will forever be unspoken, silenced by our parent’s exit. It can be a devastating and confusing loss.

Words said that can’t be taken back. Words never said that we wish could be spoken. Questions never asked. Choices never explained. Stories never told. All these and more are frozen in time for us when a parent dies. Their weight varies depending on where we are in this marathon. From being parented in infancy through the love hate race of adolescence. From the renegotiated relay of adulthood to the discomfort of accepting the baton to run this final leg of the race as our parent’s parent. And if they cross the finish line before us, to know it is ours to grieve the success and failure of their life, ours to allow them to rest in peace in their death. Ours to learn to run our own race untethered by what is now behind us.

“I am amputated, inconsolable. My father has died.

Now I must invent him, perhaps fictionalize, mythologize him.

Most of all, I will have to find a way to mourn him.

E. M. Broner, Mornings and Mourning: A Kaddish Journal

more times than any other. I reread the words looking for clues to their impact.

more times than any other. I reread the words looking for clues to their impact. fort to someone today. And when they are ready to rise and walk, stand with them and speak words of hope and encouragement. I know we will fall under the weight of loss. I believe we can stand again.

fort to someone today. And when they are ready to rise and walk, stand with them and speak words of hope and encouragement. I know we will fall under the weight of loss. I believe we can stand again.