There are a handful of books in my library that I decided to buy before I knew much about the contents, because the title was intriguing. One of those is Steve DeShazer’s Words Were Originally Magic. I thought of the title again when I decided to write about “the language of loss”. I discovered that DeShazer’s title was inspired by these words.

“Words were originally magic and to this day words have retained much of their ancient magical power. By words one person can make another blissfully happy or drive him to despair.” Sigmund Freud

I don’t know that the language of loss is magical, but it is powerful. It has the power to heal, to offer respite, to comfort. It also has the power to confuse, to limit, and at its worst to harm. Language is at the center of the things we tell ourselves, how we think out loud with others, how we experience this life. The words and phrases we use are like the weft and warp on a loom that determine the pattern and texture of the fabric. I wonder how the fabric of our grief might look if we wove it with a different language. Would it comfort us to know that our experience and expression of grief is not a sign of craziness, but a richly woven fabric of our common journey?

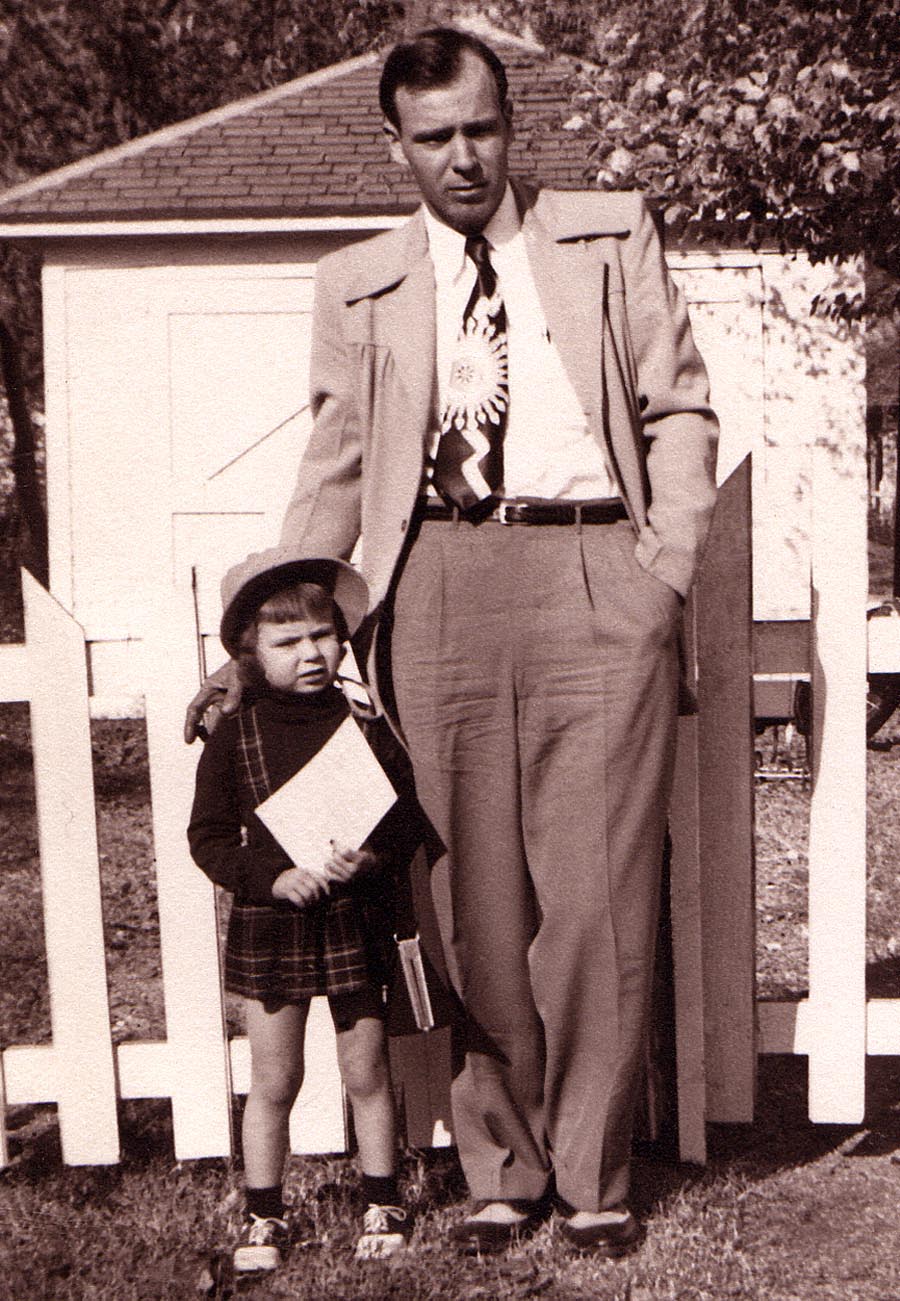

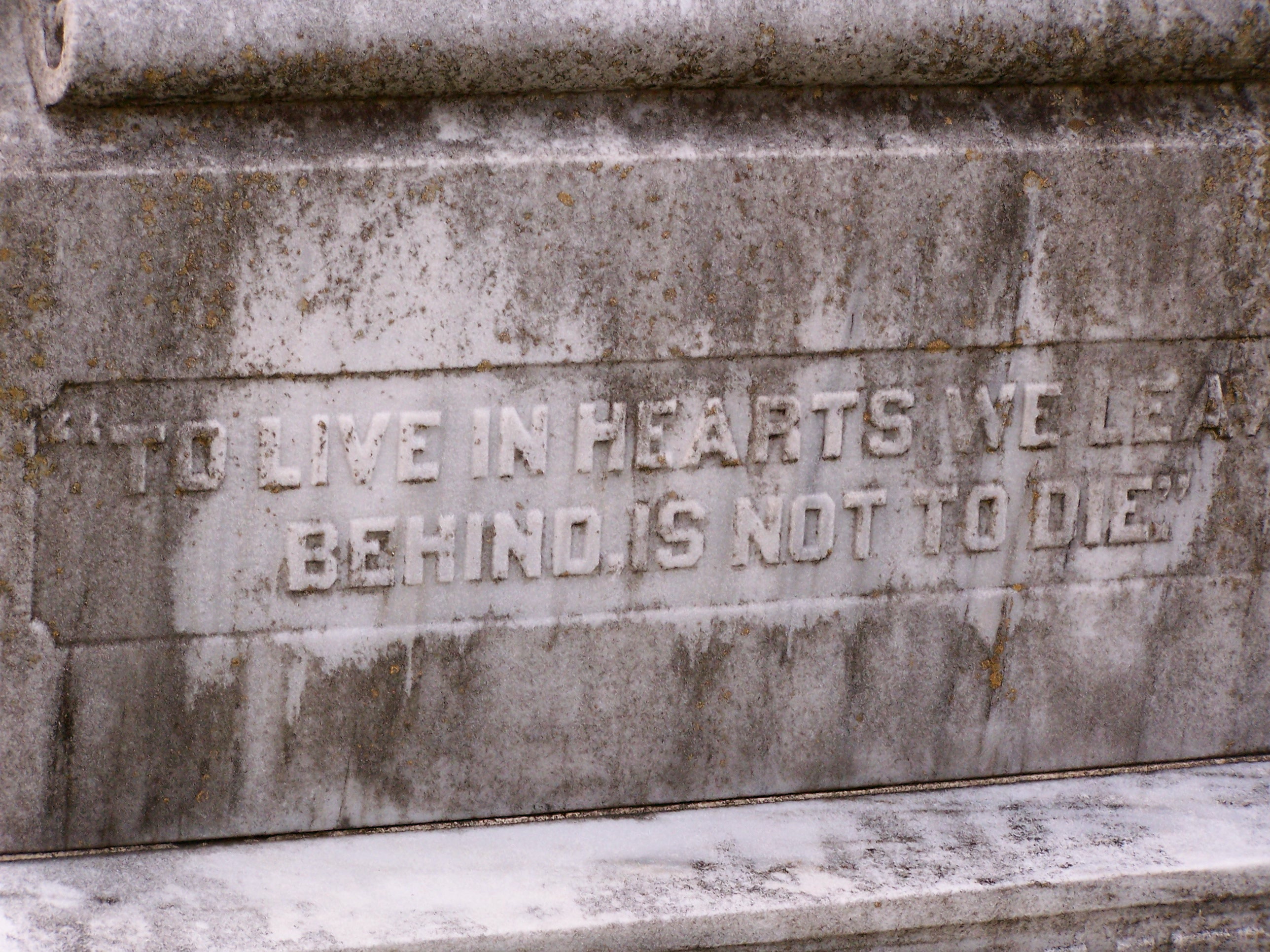

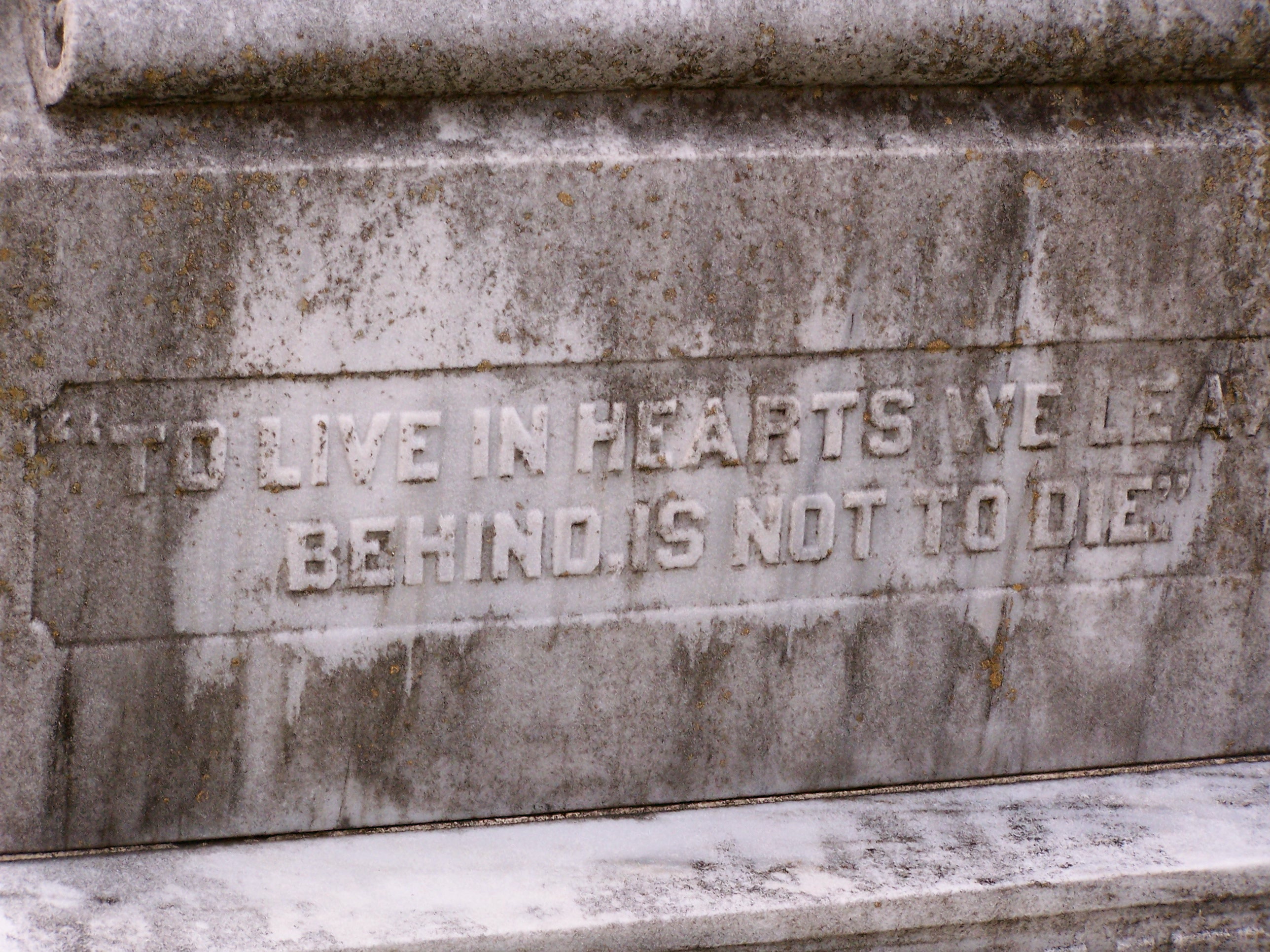

I have sat with many people over the years in moments of grief, but I can only speak with certainty from my own. I can’t say “closure” or “saying good-bye” are a help to me if they mean I will come to an end of grief, that I will be done with who I lost. If my job in grieving is to finish, and to finish means to end the relationship,…well, I’m going to avoid that finish line at all costs. I have no intention of being done with those I’ve lost. But what if our relationships are not bound by time and space. What if our grief is not about the end of relationship, but about how relationships change when death comes.

In the movie Shenandoah, Charlie Anderson, played by Jimmy Stewart, is a widower trying to keep family and home together in the midst of the Civil War. Charlie often visits the family gravesite to talk with his dead wife Martha. He tells her about the children and the war. He asks her questions and shares his thoughts. These private, intimate moments between Charlie and Martha assure us that our relationships continue beyond death. In the midst of the sadness and pain of loss, Charlie Anderson also finds comfort and the strength to continue. Even in death, Martha remains his partner for the journey.

When we don’t talk about death, we are at risk of believing that our experience of death is not only unique, but may be evidence that we’re crazy. We may worry that our ongoing involvement with our loved one means we’re “stuck” in our grief. We may also worry about what it means when some of our memory seems to be slipping away. Sometimes we can remember details of a person’s hands, can hear their voice, can see them moving, but their face begins to fade. I don’t know what it means that we can often call to mind so much about someone we love, while their face becomes a blurry, veiled image. If our eyes are windows to our soul, perhaps a face that fades in our mind is a reminder that our relationship is no longer defined by a physical body, but now fills the universe.

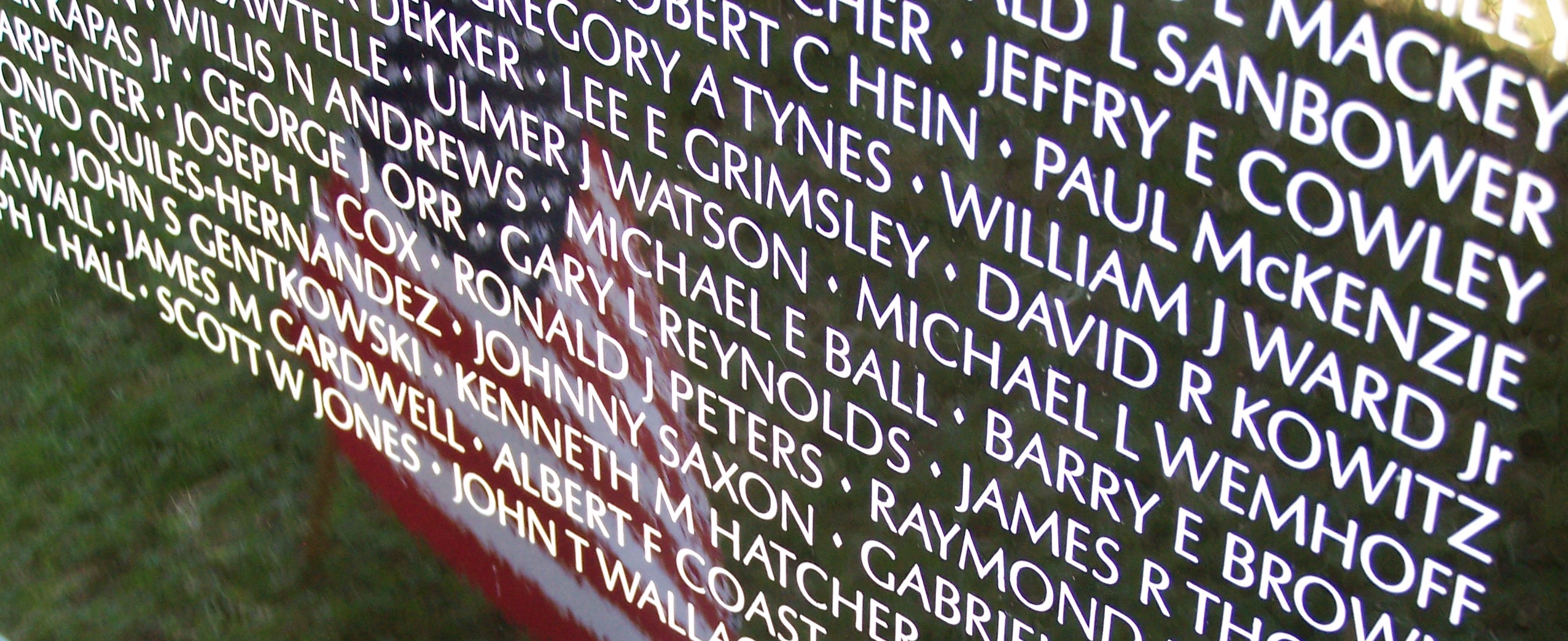

If we are going to discuss death, we need language. But experiencing loss and death is not the same thing as the language we use to describe it. Language can be concrete and limiting. Loss continues to remind us that it will not be bound by a word. That it is often gray and messy. Don’t be afraid of the language of loss. It’s the willingness to speak our loss into words that creates a language of possibility rather than limitation.

“We’re fascinated by the words–but where we meet is in the silence behind them”

-Ram Dass

more times than any other. I reread the words looking for clues to their impact.

more times than any other. I reread the words looking for clues to their impact. fort to someone today. And when they are ready to rise and walk, stand with them and speak words of hope and encouragement. I know we will fall under the weight of loss. I believe we can stand again.

fort to someone today. And when they are ready to rise and walk, stand with them and speak words of hope and encouragement. I know we will fall under the weight of loss. I believe we can stand again.