I was listening to a Hazelden webinar on adolescent suicide. The presenter talked about the importance of engaging the suicidal teen, encouraging them to talk. She identified the three most important words to say when you’re the one being told, “Sometimes I feel like killing myself.” What were the words she thought had such power to connect? “Tell me more.” Three small words with the potential to change the course of a person’s life.

“Tell me more.” Three words that invite someone to share their pain and confusion. Why are those words so often left unspoken? Perhaps because encouraging someone to hand us their pain may be the right thing to do, but it is rarely the easy thing to do. In fact the willingness to stand and hold another’s pain often leaves us facing our own discomfort.

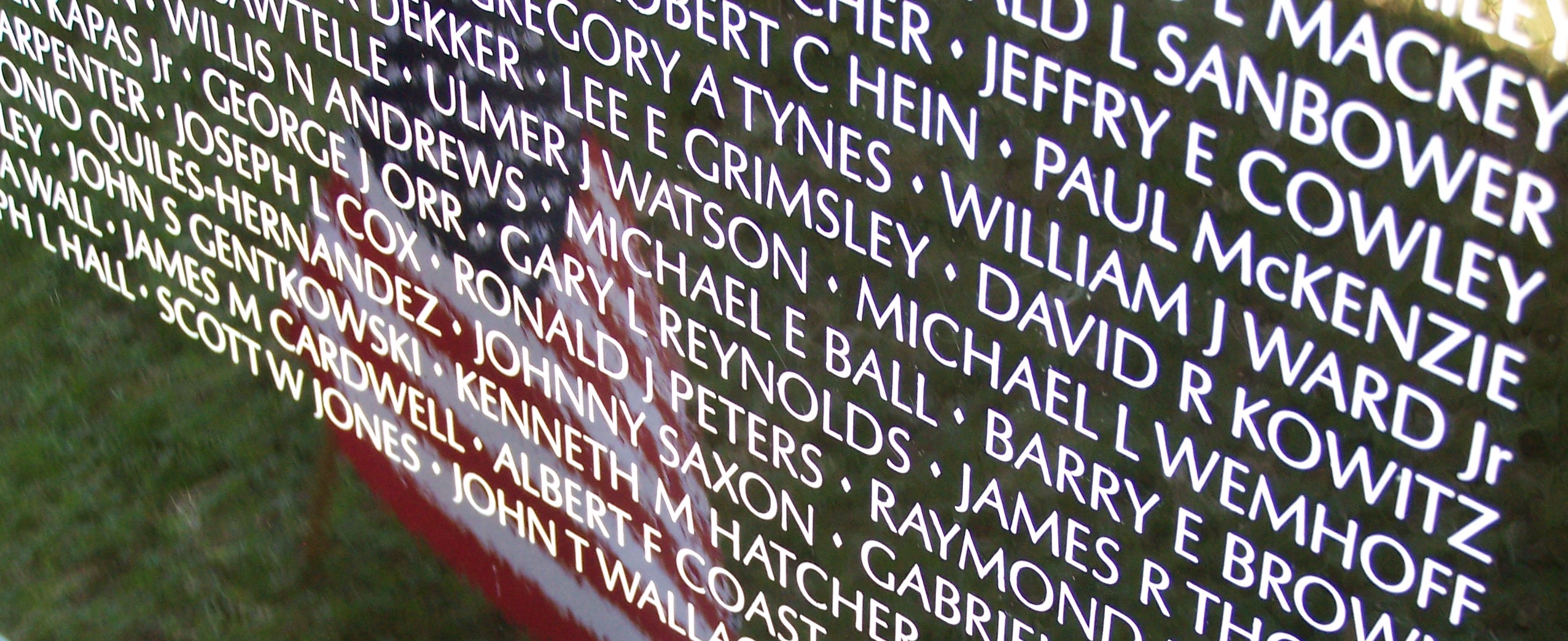

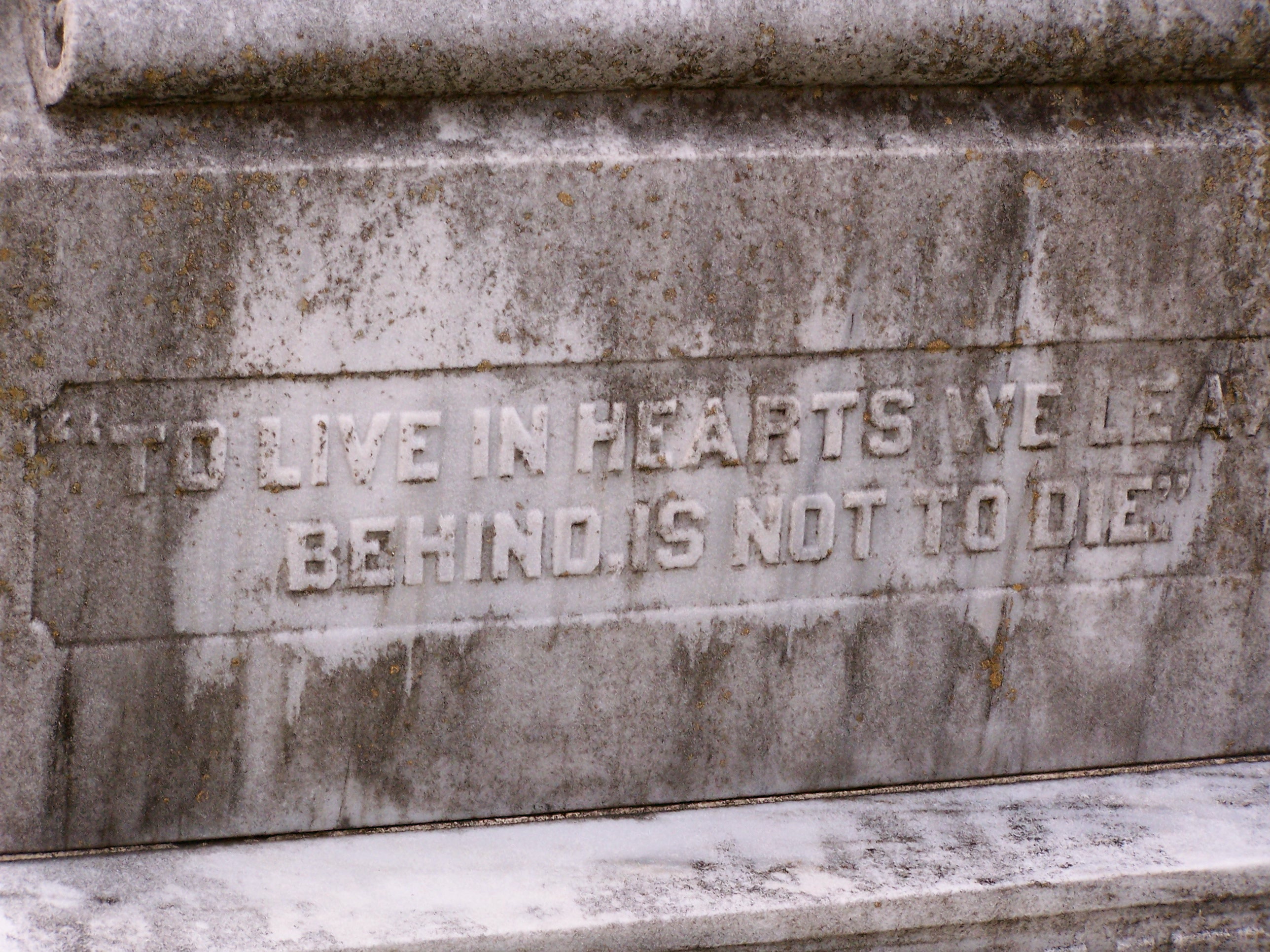

“Tell me more.” I replayed those three words as I went about my day. I thought about how they fit other situations. How powerful those words could be with those who grieve. How in the midst of grief we long for someone to ask us to tell them more about who and what we have lost. How holding the pain of someone else’s loss feels uncertain and uncomfortable, and so we hold back.

I was still chewing on the benefit and difficulty of “Tell me more”, when my weekly dose of Modern Family came on. It is Phil Dunphy’s favorite day, leap day. He has big plans to do something out of the ordinary to celebrate. But as the day continues, things begin to fall apart. Phil pulls the two boys, Luke and Manny aside in an attempt to salvage their celebration. He leans toward them and says in a low, somber voice, “I have a plan.” The boys just stand there. Phil adds, “It’s kind of traditional to lean in when someone says they have a plan.” Both boys immediately lean into the circle. No hesitation. Focused.

That’s when it came to me. What Phil Dunphy had to say was important. And when someone has something important to say, we need to lean in. To lean in and embrace what is being said, giving the words, the feelings, and the person our presence. Perhaps no territory feels more uncertain and overwhelming than the landscape of grief and loss. When we find ourselves in the presence of wounded travelers and their story, needing to lean in, our first impulse may be to just stand there. Sometimes we even step away.

Forty five years ago, John Drakeford wrote a book titled, The Awesome Power of the Listening Ear. It was a book about the “power of simply listening to others”. I think Drakeford’s intent was to help us push past discomfort to a place of leaning in. A place of inviting others to tell us their stories. What if in the presence of grief and loss, we begin to lean in, and quietly say “Tell me more.”

“Oh, the comfort, the inexpressible comfort of feeling safe with a person, having neither to weigh thoughts nor measure words, but pouring them all out, just as they are, chaff and grain together, certain that a faithful hand will take and sift them, keep what is worth keeping, and with a breath of kindness blow the rest away.” ~ George Eliot